|

|

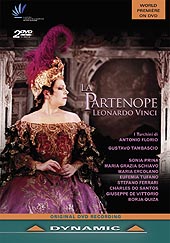

Vinci Partenope (Rosmira fedele)

Sonia Prina (Partenope); Maria Grazia Schiavo

(Rosmira); Maria Ercolani (Arsace); Eufemia Tufano (Emilio); Stefano Ferrari (Armindo); Charles de Santos (Ormonte); Giuseppe

de Vittorio (Eurilla); Borja Quiza (Beltramme). I Turchini, cond Antonio Florio. Dynamic 33686 (2 DVDs: 168’ 00”).

Coming after recent exposure to Pierre Audi’s puerile attempts to stage Gluck, this is

akin to arriving in the Elysian Fields, being a beautifully staged Baroque production by Gustavo Tambascio of a splendid opera

by Leonardo Vinci. Partenope, or Rosmira fedele to give the opera its correct name, was first given at San

Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice in 1725. It was the Neapolitan composer’s second opera in quick succession for Venice,

following the success of his Ifigenia in Tauride some months earlier. Working hurriedly, Vinci not only drew on the

recitatives used in the 1722 setting of Silvio Stampiglia’s libretto Partenope by another Neapolitan composer,

Domenico Sarro (1679-1744), but also reused some of his own arias from earlier operas. Surprisingly, despite such an ad hoc

assemblage, the opera works admirably on the stage. Already set several times and still to be employed by Handel (in 1730),

Stampiglia’s libretto was especially popular in Naples, dealing as it does with the myth of the nymph Partenope, said

to have founded Naples. The complex plot revolves around the courting of the Neapolitan queen Partenope by a clutch of suitors,

among them Prince Arsace, the former lover of Rosmira (a part first taken by Faustina Bordoni), who has herself turned up

in Naples disguised as a man to seek revenge.

The opera was first revived in modern times (as Partenope)

in an edition by the present conductor in 2004, at which time I heard it splendidly done at the Beaune Festival in a concert

performance. The high quality of nearly all the music did much to convince me that Vinci was at least as good an opera composer

as Vivaldi, a view that has further strenghtened over the intervening years. The present staging dates from 2011, when it

was given in Murcia, Spain with a cast similar to that in Beaune. In true Baroque fashion, the set makes extremely effective

use of perspective, with a view of Vesuvius in the background and an imposing palazzo to one side. The costumes and

complementary headdresses are possibly the most sumptuous I have seen in an opera production, all rich russets, golds, reds

and yellows. The singers have clearly been well coached in the art of the use of hands in Baroque theatre. My single caveat

regarding the production would be the inappropriate use of dancers in some arias, stylish though the dancing is, but the spectacular

stylised battle scene at the end of act 1 is brilliantly directed. Vocally Vinci’s arias, a judicious mix of virtuoso

coloratura pieces and cantabile writing of often languishing beauty, are mostly capably sung. Most accomplished of all is

mezzo Sonia Prina’s authoritative Partenope, but Maria Grazia Schiavi’s captivating Rosmira repeats the success

she enjoyed at Beaune, the odd uncontrolled note above the stave excepted, while Maria Ercolano’s Arsace is also fine.

Only Stefano Ferrari’s rather pallid Armindo disappoints seriously, this tenor role having been taken to greater effect

in Beaune by Makoto Sakurada. No conductor has greater insight into Neapolitan music of this period than Antonio Florio, who

directs his Turchini forces with customary élan and sensitivity. Finally, I cannot let pass mention of the delightful

intermezzo’s by Sarro, texturally augmented to cater for the delighted Spanish audience and riotously brought off Borja

Quiza and that great Italian comic actor, Giuseppe de Vittorio. This set is an absolutely obligatory acquisition for anyone

who loves 18th century opera. It should also be obligatory watching for any producer putting 18th century opera on the stage

and all those who maintain modern audiences won’t (or can’t) take historical staging. As it makes clear at the

final curtain, the Spanish audience absolutely adored this.

This review has also

been published in Early Music Review.

|